THE MARCO PERMITS

FLORIDA COASTAL DEVELOPMENT PRIOR TO THE MID 1960s

The Mackle Brothers’ business, since the days of General Development Corp. was to make home sites affordable through the "installment contract".

As described earlier, the installment contract provided for monthly payments over a long period of time and an obligation to deed the property - with the promised improvements - after the buyer had completed all the payments. The typical Deltona Corporation installment contract was for eight and a half years.

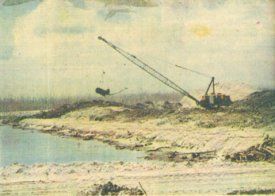

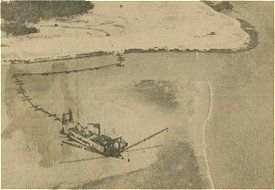

At Marco the improvements to the land typically included filling and grading of the lot, and the installation of a seawall, a road, and a water line to the property. After clearing the natural mangrove forest good fill was moved from the planned waterways into the area where it was needed by dragline or hydraulic dredge. The fill was then move to its design location by large earth moving pans and bulldozers and graded to fine tolerances by scrapers.

Like all permits - building or development - the government specifications were known and understood. If you could meet those standards you were assured of getting a permit. All specifications were clearly laid out and understood by the engineers responsible for them.

So it was for the first two thirds of the twentieth century as far as dredge and fill permits were concerned.

When development began on Marco the job of obtaining permits was a routine matter.

As it was always the Mackles' program to meet or exceed the dredge and fill standards, there was never any urgency or concern to apply for permits until the work was scheduled. Further, since permits were typically issued for three years, to apply for permits at an earlier date would be foolish since they would expire prior to the eight and a half year home site delivery date - forcing re-application a second or even third time.

Again, even dredge and fill permits were routinely granted by all jurisdictions including the Corps of Engineers.

In those days Corps permits were solely dependant upon determination that the project would not adversely affect navigation.

At Marco, the planned development of canals and waterfront property would not hinder and would in fact improve navigation.

Since man was first able to move dirt in sufficient amounts it was an admirable thing to turn swampland into something habitable.

In the first half of the century statues were erected in honor of developers converting "swamplands" into beautiful waterfront communities. Dredging and filling of mangrove swamps had been done up and down the coast of Florida since at least the early 1900s.

The Mackles themselves had developed thousands of acres of land at Key Biscayne, Pompano Beach and Port Charlotte using land and water based dredging methods.

But the knowledge of and the attitudes about those "swamplands" were changing. And Marco Island along with its developer were about to be caught up in one of the great liberal movements of the 60's and 70's - the Environmental Movement.

EARLY MARCO PERMITTING

It is true that from the start there were local " friends of the island" who resented that developers were changing their backwater nature preserve and fishing haven into a populated community. And they received a good bit of attention from the press.

The Mackles knew that they had to take special care of this special place. So - from the beginning - they were determined to be a leader among community builders in the cause of preserving the environment.

This was not the only policy it was the best policy - as it fit in to the allure of the product that they were selling - a gorgeous, nature filled - tropical resort. So their environmental protection and preservation plans for Marco were to be well ahead of other developments of the day. And - for the first year or two - the Mackles were commended - even by environmentalists - for their farsightedness.

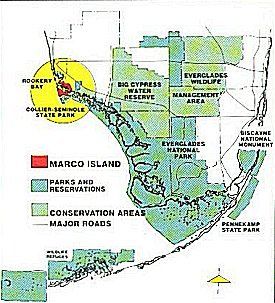

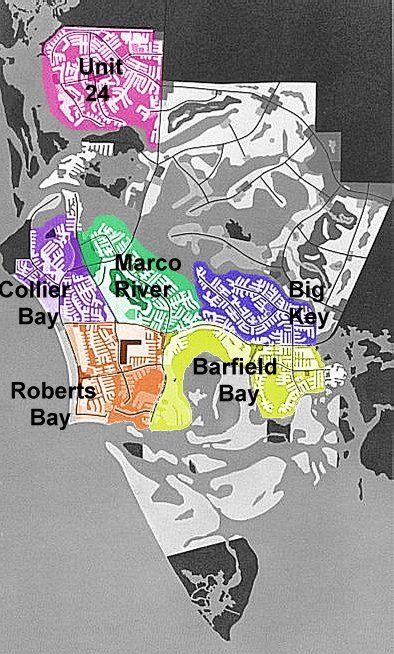

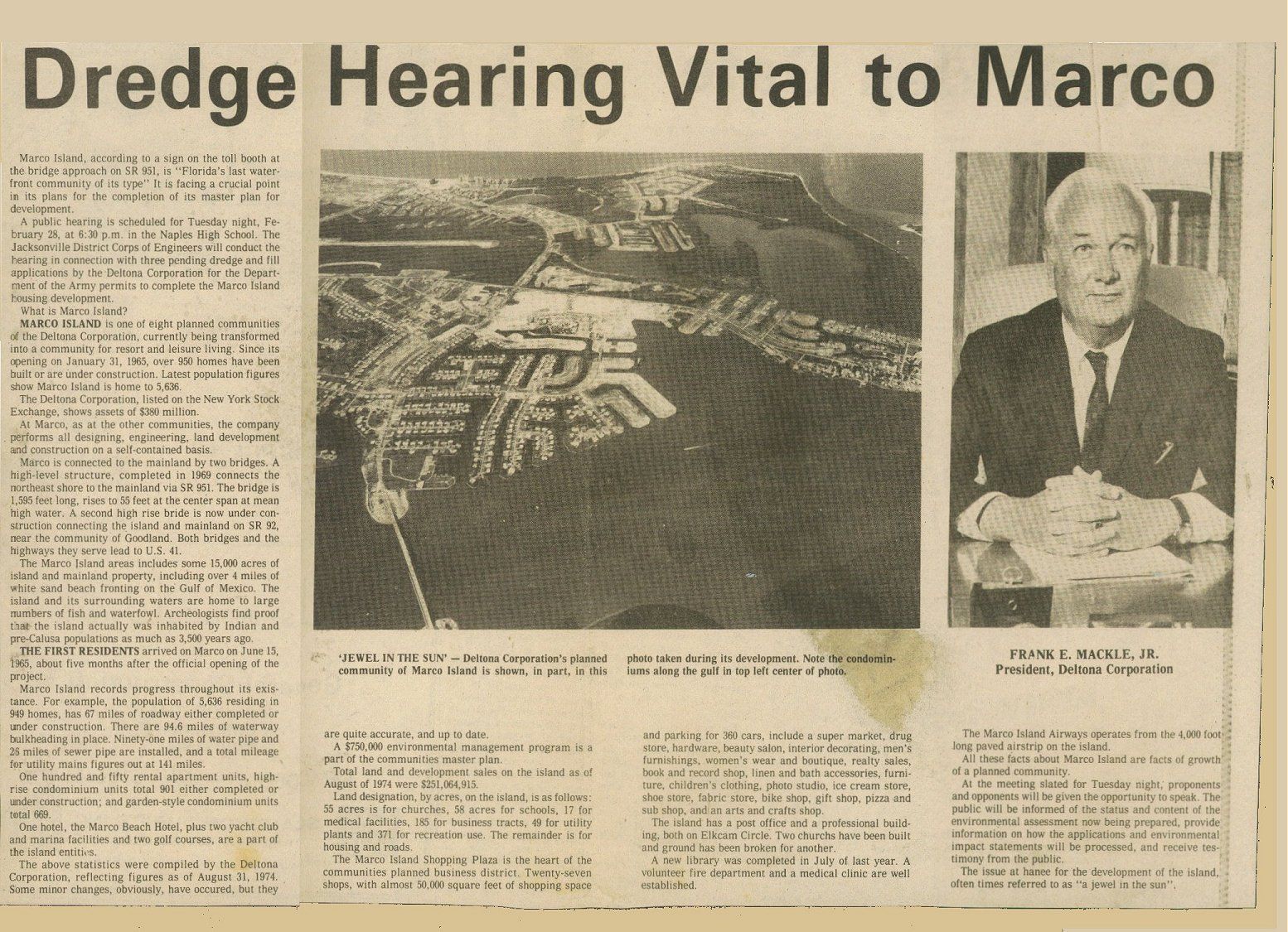

Marco Island was designed to be permitted in five permit areas: Marco River, Roberts Bay, Collier Bay, Barfield Bay and Big Key.

Marco Shores would be divided in to additional permit areas. The permit for the first phase of Marco Shores, known as Unit 24, would follow in the path of the island permits.

Soon after the property was acquired in early 1964 planning began. The opening - less than a year away would require the development of the initial "cash area" home sites and sites for model homes and a sales office. Soon after the opening the Mackles planned to open the Marco island Country Club and other island amenities. Development of the rest of the island would proceed from there in an orderly fashion.

So they set out to obtain the first permits required - the Marco River Permit.

All governmental requirements of that time were obtained in a routine fashion.

For the Marco River permit area bulkheads lines were established in October 1964. A county dredge and fill permit was issued in October 1964. The state dredge and fill permit was issued on October 22, 1964. And the Corps of Engineers’ dredge and fill permit was issued on October 27, 1964.

Six months after acquisition all permits for the first phase of Marco were in hand!

The Corps permit itself had taken nine days!

The undeveloped lots within this area were registered for sale by the State of Florida on December 31, 1964.

And the project of Marco Island and the sale of homes and home sites commenced on January 31st of 1965.

Over the next two years - with no concern for obtaining permits - all permit areas of Marco Island were released for sale. In may of 1970, Unit 24, the first area of Marco Shores, was released for sale.

After all - permits were routine.

EVOLVING ATTITUDES, REGULATIONS AND LAWS

The definition of "routine" was changing, however.

Commencing in 1967, new and revised environmental legislation and regulation had begun to be adopted. These recognized the increasing concern for the environment and were designed to insure more comprehensive reviews prior to any dredging, filling, or bulkheading tidal areas such as Marco. These and other statutes, regulation and judicial decisions expanded and lengthened the permitting process. They also expanded the claimed "jurisdiction" that agencies had over areas of development. Early on jurisdiction was to "navigable waters" or to "state lands" which were considered to be the mangrove edge. Later jurisdiction claims crept landward to include all wetlands and even " periodically wet" lands.

But the idea that all conditions - even the new ones - could not be met was inconceivable. They were only making it more difficult. Designs of water depth might have to be modified. Seawall design might have to be altered. Ways to insure water quality might have to be adopted. It might be more costly but the company was willing to meet the revised standards.

Just tell us what they were.

.....

Several major new state and federal environmental protection laws were passed which began to seriously impact the approval process.

In 1967, Chapter 253, of the Florida Statutes, was substantially revised to provide for detailed environmental state review.

In January 1970 the National Environmental policy Act was passed by Congress which required the preparation and review of an environmental impact statement.

In April of 1970 the Federal Water Quality Improvement Act was passed by the Congress of the United States.

In 1970 the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was created. And - later the EPA was given veto power over permitting decisions of the Corps of Engineers.

In 1972 the Federal Water Quality Improvement Act was amended by passage of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act. As a result it was mandated that, as a condition precedent to application for a Corps permit, that the responsible state agency certify that there is reasonable assurance that the dredging and filling activity will not violate applicable water quality standards. This approval became known as "Water Quality Certification". This new requirement obligated Deltona to undertake massive studies, engage in protracted hearings, and present evidence of satisfactory water quality.

These laws were all designed to protect the environment.

Still, even land sales regulators did not deem them a threat to the sale and delivery of installment land sale contracts. It was only in October of 1973 that the Florida Land Sales Law, Chapter 478, Florida Statutes, was amended to require, for the first time, that necessary environmental approvals be received prior to registering properties for sale with the state.

Even then - existing registrations were not held to the same requirement.

For new projects just starting out the new regulations could be dealt with. And while a great deal of interpretation would still evolve at least they would know what the "rules of the ballgame" were before opening a project for sale.

Deltona did not have that luxury. We were already committed to a design and to sales contracts that had been entered in to years before these laws were even contemplated.

And there were no "grandfather" clauses. There were no provisions to deal with the Marco type of situation where planning, development and sales had already commenced.

On top of the new laws agency rules and jurisdictions were being re-interpreted and enforced by the environmentalist who headed up the local, state and federal permitting agencies. These re-interpretations were done without legislative involvement. Often it took a court battle to resolve whether the agency had over-reached their authority or not. But until it went through the court system their interpretation would be used.

So as the new laws went on to the books Deltona continued its very successful marketing of home sites - and promising that improvements would be made on schedule.

Nothing in the new laws said you couldn't develop wetlands. They were just redefining the process of obtaining the permits.

By the end of 1969 seventy seven percent of all Marco Island home sites had been sold.

Ninety five percent of the island had been sold by the beginning of 1970.

DELTONA GEARS UP FOR THE PERMIT BATTLE

By the late 60's Dad knew he had a fight on his hands.

The Marco River permit had been routine.

The next one necessary to the orderly development of the island was the Roberts Bay permit.

By now the voices of the environmentalists were getting louder. The Corps of Engineers were still operating under the 1899 Rivers and Harbors act which gave them authority over "navigable waters". But they were beginning to be pushed.

In July of 1967 - as a result of mounting concerns for the nations wetlands - the Corps entered into a Letter of Understanding with the Interior Department whereby a full scale Washington level review would be required on any permit of which the Interior Department did not approve.

Still, it was just a review and Interiors' role was simply advisory. The Corps would still make the final decision. And this was the same Interior Department that - in October of 1964 - had issued a letter from their Fish and Wildlife Service to Deltona for its " responsible development plan" and even suggested that Deltona communicate its story to conservation organizations and magazines!

Nevertheless, Interior - with its new permitting role - did oppose the Roberts Bay dredge and fill proposals.

During the processing of the Roberts Bay permit the state had revised - in 1967 - Chapter 253, of the Florida Statutes. Detailed environmental state review would now be required for dredge and fill permits.

Dad and Jim Vensel began to see "the writing on the wall". They faced the fact - during this process - that permits would require a much greater effort in order to meet the promises we had made to Marco customers.

Dad employed the small but prominent Tallahassee firm of Peeples & Moore. Jack Peeples and Ed Moore became close allies in the battle for Marco permits.

The Roberts Bay dredge and fill permits were routinely approved by the county in February 1968. The state permits - in spite of the newly revised state laws were routinely granted in April of 1968.

The Corps permits for Roberts Bay were applied for in September of 1967. Between then and December of 1969 when the Corps issued the Roberts Bay permits the process was beginning to change significantly.

At the same time the Corps and state and Federal agencies began altering and re-interpreting existing rules and regulations to a more stringent "environmental protection" bias. Dredging and drag line operations were scrutinized more closely. Rules were being put in placed and enforced which did not exist a couple of years earlier. Conflicts arose.

During the processing of the Roberts Bay permits the company had been doing as much as it could on Marco in areas which did not require permits. Jurisdiction still ran only to the edge of the mangroves - not to other privately owned lands uplands of "navigable water".

Two incidents which exemplify the changing relationship with the Corps and the creeping jurisdictional claims that were in process are described in Douglas Waitleys book, "The Last Paradise". These kind of complications characterized the on-going development process for the remaining years of the Marco dredge and fill activities.

"The Saga of the Landmark Waterway Dredge

Work in a certain portion of Roberts Bay area did not need a Corps permit. this area included the large Unit Seven swamp, bounded by SR 92, South Collier, South Heathwood, and Winterberry. Operations here had started in 1967.

Once in the Unit Seven swamp, the dredge sucked huge amounts of material from the bottom and deposited it in three areas. The first was along the swamp's western edge, where it formed such short projections as Tulip, Birch, and Aster Courts. At the same time the aircraft landing strip was converted into Landmark Street (at which time a new landing strip was opened in the Unit Six swamp along what would become Edgewater Court.) On the eastern edge of the swamp a second series of landfill courts was created running off Heathwood. these included Shenendoah, Whiteheart, Mistletoe, and Treasure. finally, in the middle of the swamp, dredgings were poured onto a finger of pre-existing, semi-dry land to form Lamplighter Court and its appendages such as Coronado, Lighthouse, and Driftwood Courts.

By Autumn 1968 the land contract requirements had been met in the former swamp, and Deltona wished to move the dredge into other areas requiring attention. It would seem a simple matter to dig a channel south so the dredge could exit into Roberts Bay. But the Corps, under prodding from the Department of the Interior, now declared its jurisdiction covered not only by navigable water but the shorelines of this water and waterways leading to the shoreline.

Under these new rules the Corps denied Deltona the right to cut a channel south to permit the dredge to leave the Landmark area. neither would the Corps permit Deltona to send the dredge back north the way it had come and exit through the channel it had may (and since plugged up) to Collier Bay. The dredge was effectively bottled up and useless. To make the matters worse, Deltona was renting the dredge for $3,300 per day!

Deltona wrote the Corps about the "dire emergency" relating to the dredge and the fact tht the exit channel would pass through a mainly swampy area that had no value in terms of navigable waterways. The Corps finally relented and Deltona dug south from the Landmark Waterway to where Winterberry Drive would be constructed, and then followed the future Heathwood until the dredge exited into the Roberts Bay channel between Forrest and Quintara Courts. it had taken twenty eight days to complete this simple act and had cost Deltona $92,400 in unnecessary rental payments.

The Run-In over Frederick Bay

Deltona was now desperate to complete its obligations under the Coordinated Growth contracts. The state had long ago approved its bulkhead lines, which set the parameters for the island and along which the mosquito dikes had been built. Because hitherto the Corps had jurisdiction only over the navigable waters outside of the bulkhead lines and because Deltona owned outright all the territory within the bulkhead lines, the company believed it had the right to begin digging the slips and waterways within the bulkhead line. Accordingly, the now-released dredge was put to work in Frederick Bay, a small, virtually landlocked swamp at the extreme southeast tip of the island.

This caused a run-in with the district Corps agent, who inspected the area via helicopter late in August 1968. He warned that the Corps now considered such activities illegal and that in performing them Deltona opened itself to prosecution. The company had no choice except to stop work at the site, sealing the mouth of the waterway with an earthen plug."

Work in a certain portion of Roberts Bay area did not need a Corps permit. this area included the large Unit Seven swamp, bounded by SR 92, South Collier, South Heathwood, and Winterberry. Operations here had started in 1967.

Once in the Unit Seven swamp, the dredge sucked huge amounts of material from the bottom and deposited it in three areas. The first was along the swamp's western edge, where it formed such short projections as Tulip, Birch, and Aster Courts. At the same time the aircraft landing strip was converted into Landmark Street (at which time a new landing strip was opened in the Unit Six swamp along what would become Edgewater Court.) On the eastern edge of the swamp a second series of landfill courts was created running off Heathwood. these included Shenendoah, Whiteheart, Mistletoe, and Treasure. finally, in the middle of the swamp, dredgings were poured onto a finger of pre-existing, semi-dry land to form Lamplighter Court and its appendages such as Coronado, Lighthouse, and Driftwood Courts.

By Autumn 1968 the land contract requirements had been met in the former swamp, and Deltona wished to move the dredge into other areas requiring attention. It would seem a simple matter to dig a channel south so the dredge could exit into Roberts Bay. But the Corps, under prodding from the Department of the Interior, now declared its jurisdiction covered not only by navigable water but the shorelines of this water and waterways leading to the shoreline.

Under these new rules the Corps denied Deltona the right to cut a channel south to permit the dredge to leave the Landmark area. neither would the Corps permit Deltona to send the dredge back north the way it had come and exit through the channel it had may (and since plugged up) to Collier Bay. The dredge was effectively bottled up and useless. To make the matters worse, Deltona was renting the dredge for $3,300 per day!

Deltona wrote the Corps about the "dire emergency" relating to the dredge and the fact that the exit channel would pass through a mainly swampy area that had no value in terms of navigable waterways. The Corps finally relented and Deltona dug south from the Landmark Waterway to where Winterberry Drive would be constructed, and then followed the future Heathwood until the dredge exited into the Roberts Bay channel between Forrest and Quintara Courts. it had taken twenty eight days to complete this simple act and had cost Deltona $92,400 in unnecessary rental payments."

The rules of development were changing day to day as the Roberts Bay Corps of Engineers permit process dragged on.

In September 1968 - after a lengthy review of the permit issues - the Interior Departments Fish and Wildlife Service recommended denial.

Dad - for one of the few times in the whole permitting process - sought out political assistance. His friend Senator George Smathers - a long time visitor to the Key Biscayne Hotel - was approached as well as Florida's other Senator, Spessard Holland. They both expressed their support for the project to Russell Train, head of the Interior Department, and to the Corps of Engineers.

Russell Train was not moved.

Nevertheless - in spite of Interior Department objections - in December 1969 the Corps issued the Roberts Bay permit. They based their decision on their historical mandate to enhance and protect navigable waters.

But it had taken over two years - compared with nine days for the Marco River permit area.

And there had been a cost. The Corps - beginning to feel the influence of the environmental movement - had extracted promises from the company to reduce the amount of fill to be dredged as well as to preserve a small mangrove island named John Key in Smokehouse Creek and to construct a man-made mangrove island in the middle of Roberts Bay as an experiment in environmental research.

Significant in the Roberts Bay permit - the meaning of which was debated many times over the next seven years - was an admonition from the Corps that "The granting of this permit does not necessarily mean that future applications for work in the same area will be similarly granted."

There was no special victory celebration. While the permit process was absorbing more of Dad time and Jim Vensels time than in the past and legal and other support was expanding permits were still considered a routine - if more involved - process.

The 1969 Deltona annual report issued in the spring of 1970 contained not a word about permits or environmental matters. We weren't trying to hide anything. We simply did not - and would not until 1976 - have any doubt about permitting. It was still only a small part of the huge effort under way in the much larger on-going efforts to plan, design, sell and construct just one of the many Deltona master planned communities.

To better deal with the growing effort necessary to obtain all Marco permits the company continued to expand its internal and external resources.

In 1970 the company established a Department of Environmental Management headed by George Spinner a noted marine biologist under the direction of Jim Vensel.

The company also established the Marco Applied Marine Ecology Station (M.A.M.E.S.) and built a modern laboratory building located on a waterway in the heart of Marco Island. A five year budget of $850,000 was established which among other things funded a study to determine the kinds and quantities of plant and marine life in the Marco area, a joint program with the University of Miami to survey marine resources, a series of artificial reefs, the establishment of mangrove forests in shallow waters starting with the Roberts Bay area and the erection of artificial nests for bald eagles.

In 1971 Jack Peeples was persuaded to join the company as head of the Legal Department. Jack was soon recruiting the best and brightest young attorneys as he staffed up the department for all company legal matters but especially the pursuit of the Marco permits. Jack was also named to the Board of Directors at the same time.

Between the Legal department and the engineering department a myriad of outside consultants were hired to monitor work and redesign the new permit areas to meet the changing standards and to argue their merits in the many public hearings.

Land development activities at Marco were altered to conform to the stricter requirements of the new permits and the evolving rules of the various agencies now overseeing the work. Keeping silt from intruding on the natural waters around Marco became a major concern. Work was now done exclusively behind dikes whenever possible. When diking was impossible polyethylene barriers called "diapers" were strung around dredging operations. dredge captains had to be sensitive to currents which might degrade the "diapers" or render them ineffective. Any evidence of silt beyond the diapers was a cause for the entire dredging operation to be stopped.

TWO MAJOR STATE DECISIONS - THE WAR IS WON ........ TWICE!

While the struggle became harder and longer - every battle we fought - until April 1976 - resulted in a victory.

After Marco River and Roberts Bay had been successfully obtained four permit areas remained. Each area required county, state and federal permits. Many of the permits were multi-faceted. Each area and each part of each permit were pursued. Even the attached "Permit Detail and Chronology" chart does not begin to show the many steps that had to be negotiated for each permit. Environmentalist, independent environmental groups such as the Audubon society, the Nature Conservancy and the Sierra Club as well as the environmentally biased agency staffs now opposed every permit. Their opposition grew to the level of a crusade - one of many in the growing Environmental Movement.

In other arenas they were changing the way the United States looked at every enterprise. In Arizona they were protecting the scenic mountain ranges. In Wyoming they were protecting the scenic rivers. Nuclear power - once thought of as a boon to mankind was being opposed on environmental grounds. Oil companies were under fire as a threat to the environment.

In Florida it was the wetlands that were prized.

None of these crusades were wrong.

We were environmentalists. We loved Florida as much as anyone. The Mackles whole business life had been spent extolling the virtues of the Florida environment. As the science - and the regulation - of the wetlands evolved over the next few years - and developers knew what the new rules were - they would be designing future communities with more than what was required in the way of the protection of the environment.

What we needed now was someone to recognized the quandary that we had been caught in.... someone to bring an element of wisdom ... and justice ... and reason to these unique issues that were Marco Island.

It seems, however that these movements - no matter how noble their cause - often ignore other principles that were once held dear.

Time and again the opposition gave lip service to the plight of the Mackles. Time and again they commended us for our efforts to do what is right. Time and again they recognized that we were unfairly caught in the middle of this movement. But they were unwilling to compromise in any way. Such is the nature of crusaders.

The Governor of the state and the State Cabinet understood the fix that we - and the State - were in. And they recognized that the State of Florida had a stake in the resolution of the matter. The Mackles had been recognized as outstanding developers for over twenty years. Dad and Elliott had been instrumental in creating the early regulatory authorities over the development industry. The state had permitted us to sell the land at Marco through their Division of Installment Land Sales. The county had already granted permits to develop Marco. Thousands of their constituents supported the development of Marco.

The State - through its Land Sales regulation was in the business of seeing that developers delivered on their promises. With Deltona - it seemed - government agencies were obstructing a company from doing that very thing!

At the same time the state was emerging as a strong protector of the Florida environment. And no politician wanted to oppose the emerging public concern for the wetlands.

And so the Governor and the Cabinet were amenable to a solution - a compromise - between the developers and the environmentalists.

The opportunity was now in their hands.

The Collier Bay, the Barfield Bay and the Big Key permits had made it through the county processes and were now in Tallahassee for state approval. Controversy over the matter resulted in the larger Marco development issues coming before the Governor and the State Cabinet which in matters such as these sat as the Trustees of the Internal Improvement Fund or T.I.I.F. or more often the I.I.F.

Unfortunately, the executive director for the I.I.F. was the newly appointed Joel Kuperburg. His most recent job was as head of the Collier County Nature Conservancy an arch enemy of Marco Island!

Still he had to answer to the Governor and the Cabinet.

After application and review by the staff of the I.I.F. a series of hearings before the Cabinet ensued wherein Kuperburg made his recommendations and the company presented its arguments.

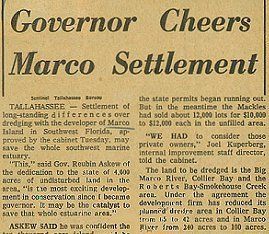

There emerged from the Cabinet meetings and private conversations with the Governor and his staff the concept of resolving all issues surrounding the Marco project in one massive State Settlement.

The Company was willing to reduce the original scope of the project significantly and we were further willing to deed over significant and very valuable - both economically and environmentally - lands to the State for permanent preservation.

The Governor was positive about the solution. Key legislators and Cabinet members were on board.

But the devil was in the details!

Time and again we thought the matter had been resolved. But time and again Kuperburg and his staff blocked or altered the proposed settlement.

All through 1971 and 1972 the matter came before the Cabinet again and again. Several times it was thought that agreement had been reached. But again and again new issues arose and new obstacles had to be overcome.

Finally, in October 1971, a settlement was reached.

The Cabinet voted unanimously in favor of the Marco Settlement!

The state would grant the three permits. In return the company would deed to the state the Kice Island property and - when all permits had been received from State and Federal agencies - the company would deed another 4,000 acres of Marco to the State of Florida.

The battle had been won!

Victory was ours!

All other obstacles would be easy to handle now that the Governor and the State of Florida had settled the matter. Surely the weight of this lofty body would bring everyone together.

But that was not to be the case.

There was a huge outcry by the environmentalists.

We had not seen the last of them by a long shot!

And they would have another shot at us as a result of the new obstacle that had been created in 1970 - the Federal Water Pollution Control Act which would require us to obtain a Water Quality Certificate before going to the Corps of Engineers for the final permit.

In the meantime they would hold our feet to the fire as we continued to do what we could to deliver home sites at Marco.

So Dad and his legal and engineering staffs began gearing for the second battle with a state agency - this time the Department of Pollution Control for the federally mandated Water Quality Certification.

From that point on, in spite of having state permits in hands, the "Water Quality Certification" was the final test and would be the critical and decisive battle for the permits. The certification - issued by the States Department of Pollution Control (DPC) was mandated by Federal law as being required before Corps permits could be obtained. The State had already blessed the Marco development with the historic State Settlement. And - as the Corps had never denied a major permit that had come to its desk - the Water Quality Certification would do it! The rest would be routine.

The company put out an enormous effort to obtain the Water Quality Certificate.

This process more than any other brought the scientific debate to the forefront as each side presented data to support or to block the creation waterfront property at Marco Island.

The M.A.M.E.S. laboratory data - now accumulated for several years - was the basis for the company's arguments. Experts from universities and the private arena were hired. Legal staff was bolstered again.

Massive studies were done, protracted hearings took place, and present evidence of satisfactory water quality.

And a year and a half after the State Settlement and a long public hearing the Board of the Department of Pollution Control - meeting in Tampa - made its final decision.

On April 10, 1974, in a 3 to 1 vote granted the Water Quality Certification for the Collier Bay, Barfield Bay and Big Key permit areas.

All that was left was the Corps permit and we had the required Water Quality Certificate in hand. And "after all" the Army Corps of Engineers was "the biggest dredger and filler on the planet" .... "they were engineers just like ourselves"

And ...sooner or later... "justice would prevail".

All county permits and approvals had been obtained.

All state permits and approvals had been obtained.

The federally mandated "Water Quality Certificate" had been obtained.

Sure the Corps was more environmentally sensitive than ever.

But they had never denied a major dredge and fill permit application.

Victory was ours .... again!

THE CORPS OF ENGINEERS

Only the Corps of Engineers permit remained.

We were aware of the EPAs new veto power over the Corps.

But it had never been used.

In spite of the victories at the State level the development delays had been great. And the Corps permits were still two years away.

Sales had been brisk from the start.

By the end of 1971 approximately 12,100 lots had been sold for $134,500,000.

By the end of 1972 approximately 13,200 lots had been sold for $154,100,000.

By the end of 1973 approximately 13,900 lots had been sold for $167,922,000.

Of them only 3,320 were delivered at that point.

But many of the undelivered lots were coming due. The eight had half years had run. Contracts were being paid in full.

At the end of 1973 - because of the agonizing delays in the permits - all unsold Marco Island and Marco Shores lots were taken off the market.

At that time there were approximately 10,600 sold but undeveloped lots at Marco Island and Marco Shores. Approximately 6,500 to 7,000 sold lots were in the Big Key, Barfield Bay and Unit 24 permit areas. Due to cancellations caused by the delays that number would diminish somewhat between 1973 and 1976 when the Corps decision finally came down. By that time there would be approximately 6,000 contract holders in those areas still waiting for their deeds.

The other undelivered lots were either in the Collier Bay area - where permits would be granted - or in the previously permitted areas of Marco.

At the end of 1973 the oldest undelivered lot contracts were nine years old - already six months late in delivery.

The story of the loss of inventory, the blow to the sales force and the cancellations that began to mount on existing contracts - all in the midst of an energy crisis and recession - is told elsewhere. For now it is sufficient to say that the financial impact of the delays was already quite serious.

But that would all be fixed once the Corps of Engineers dredge and fill permits were granted.

So the Corps permit process began.

Applications were submitted.

The Water Quality Certificate was submitted.

The Corps Environmental statements was published.

Deltona was informed in July 1975 that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) "may also seek to assert regulatory jurisdiction."

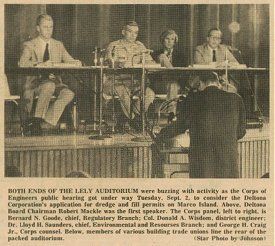

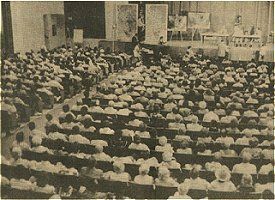

On September 2nd and 3rd, 1975 public hearings on the Corps of Engineers permits were held at the new Lely High School in Naples, Florida.

Dad and Jack Peeples spared no expense or effort. They set out to round up as much support for the company's position as possible. Civic groups were contacted. Letters to the Corps from interested friends were solicited. Even the unions - not always the closest friends of Deltona - were urged to support the effort. And to their credit they showed up in great numbers.

Letters of support were encouraged. Douglas Waitley, in his book The Last Paradise, says that letters to the Corps supporting the development of Marco outweighed opposition letters 11,900 to 1,217 !

Six weeks before the hearing Dad led a major press conference at Marco intended to communicate our position.

On September 2, to make sure that company support was evident at the hearing, busses were lined up to transport Marco friends to the hearing.

The hearing lasted two days.

Colonel Wisdom, as head of the Corps' Jacksonville office, presided over the hearing.

On the stage with Colonel Wisdom - among others - was a representative from the EPA.

They recognized that this was a precedent setting hearing - the first where it would be decided if a private company had the right to develop wetlands that did not involve navigational waters without government restrictions.

Testimony went on for two full days with each side putting on their evidence and the public testifying as well.

The hearing concluded late in the afternoon of the 3rd of September 1975.

The wait began.

The Corps review process was done internally at three levels.

And a typically hush-hush military process took over.

Applications had been made to the Jacksonville office.

Over the next seven months the permits made their way through the Corps offices. We had very little input after the public hearing.

Jacksonville made a very ambiguous recommendation to Atlanta offering alternatives rather than recommendations.

Atlanta - more decisive - made a recommendation for approval of all three permits to Washington.

Now we were almost home!

Washington began their review in strict privacy.

For the Corps - it turned out - the threat of a veto from EPA was critical. A veto - only recently made possible through Federal law and never before used - would be an embarrassing assault on their authority and would clearly put them in opposition with the environmental movement.

In spite of the Atlanta recommendation and under the threat of the EPA veto, the Corps of Engineers, on April 16, 1976 made their decision public.

They looked at it as a compromise.

They would grant the Collier Bay permit.

And they would deny the Big Key and Barfield Bay permits.

While it was not a part of the decision, the trailing Unit 24 permit had been effectively denied as well.

6,000 promises could not be kept!

The National Geographic and other publications hailed the Corps' decision at the time as "landmark" and "precedent setting".

It was the first time in history that the government had denied a private property holder the right to fill coastal wetlands.

The decision - eventually upheld by the highest courts in the land - as of April 16, 1976 - ended the filling of coastal wetlands in the United States.

Dragline Operation

Hydraulic Dredge Operation

Marco relative to other State, Federal and privately protected lands

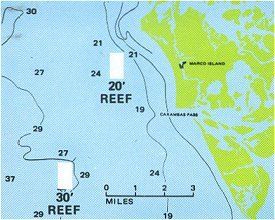

Marco Permit Areas

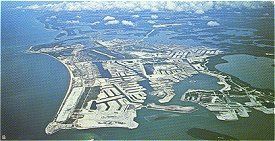

Marco Island 1969

Roberts Bay Permit Area

in Foreground

M.A.M.E.S. Building - Marco

M.A.M.E.S. Laboratory

Artificial Fishing Reefs

Man-made mangrove Island in Roberts Bay

Marco 1972

Completed Roberts Bay in Foreground

"The biggest dredger on the planet"

The Rules Change Again

April 1974

Corps Hearing

September 2 & 3, 1975

The Deltona Years:

A gentle dream shattered

By Marion Nicolay

Special to the Eagle